Robin DR401 to Corsica and Elba

September 2015

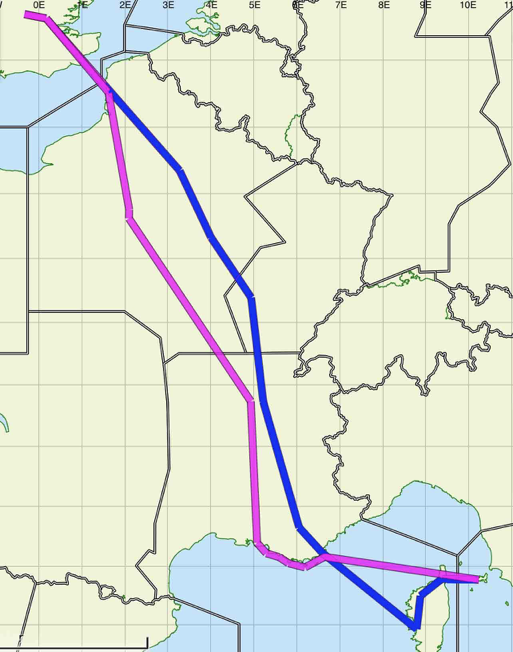

The plan was to fly to Corsica the day after the Robin fly-in at Elstree on Saturday 5th September, meet up with our two sons for a week’s holiday, then take a couple of days in Venice on the way back via meetings in Darois and Paris.

Because our new DR401 155CDI demonstrator was still in build and because of weather uncertainties, Jennie and I had made the unappealing train journey to Dijon to ferry the Robin workshops 155CDI demonstrator (F-GNXT) to the UK the weekend before the fly-in, Guy Pellissier flying the Avgas fuelled 160 hp Swiftwing model (F-GLDK) over on the day.

The plan was to fly to Corsica the day after the Robin fly-in at Elstree on Saturday 5th September, meet up with our two sons for a week’s holiday, then take a couple of days in Venice on the way back via meetings in Darois and Paris.

Because our new DR401 155CDI demonstrator was still in build and because of weather uncertainties, Jennie and I had made the unappealing train journey to Dijon to ferry the Robin workshops 155CDI demonstrator (F-GNXT) to the UK the weekend before the fly-in, Guy Pellissier flying the Avgas fuelled 160 hp Swiftwing model (F-GLDK) over on the day.

On Sunday, we flew the two aircraft in formation back to Darois, then Jennie and I refuelled and departed for Ajaccio in the 160, F-GNXT being required for demonstration purposes at the factory.

F-GLDK was built as a test-bed to certify the new Swiftwing and so has what would have been considered a full set of instruments in the 1920s—an altimeter and an airspeed indicator. The secondary benefit as a demonstrator is that there is a large expanse of virgin panel for people to imagine how they would fill it. This works fine for the customer because all the panels are custom-configured but the prospect of flying a couple of thousand nautical miles over Europe spread over two weeks without an attitude indicator was not the happiest.

The Dijon controller confirmed that he had activated our flight plan and we proceeded south. Passing Lyon on our right, we got clearance through the restricted zones that virtually fill the area adjacent to the southern French coast (being Sunday helped). The Cannes controller said that our flight plan had not been activated, so she did so in time for us to start the 120 nm crossing of hazy mediterranean. It was here that we really started to miss the AI. Flying without one in these conditions was a bit like going to the dentist: there may be no pain but it just doesn’t feel comfortable. A feeling that was to be amplified on the return trip.

Corsica eventually presented itself through the haze and, after routing via various VRPs, we joined cross-wind to land at the Napoleon Bonaparte airport at Ajaccio. Not much happening there: quite a few GA aircraft sitting around on the immaculate tarmac, ranging from small singles to twin turbo props and light jets, and just the occasional EasyJet or Air Corsica flight, so fairly typical of a French regional airport.

Corsica eventually presented itself through the haze and, after routing via various VRPs, we joined cross-wind to land at the Napoleon Bonaparte airport at Ajaccio. Not much happening there: quite a few GA aircraft sitting around on the immaculate tarmac, ranging from small singles to twin turbo props and light jets, and just the occasional EasyJet or Air Corsica flight, so fairly typical of a French regional airport.

We were met by the GA services minibus: crew are allowed to walk on the apron, but to go to the terminal (less than 100 metres away) minibus travel est obligatoire. The minibus crews were very accommodating, however, taking us through security to drop us off outside the car hire office, all tout compris.

We anticipated arriving about the same time as our two sons, who were coming by Air France / Air Corsica via Paris (we had left home simultaneously). An exchange of text messages revealed that they were, however, still at Paris Orly. Their flight to Charles de Gaulle had been delayed, they missed the connection at Orly and Henry’s suitcase had disappeared—along with 19,999 others on that day alone because of a scanner malfunction at Charles de Gaulle! After chasing us around Europe for a while the bags finally caught up with us at home 28 days later.

With the family re-united just before midnight we had an excellent week in Corsica and Henry discovered the meaning of travelling light. Sadly, our plan to fly to Corte in the interior was thwarted by it being closed until the end of the year for renovation, but we did tap into local knowledge about the best way to get there. Corte is at 1,100 feet AMSL with peaks up to around 6,000 feet immediately to the West and 3,000 feet to the East. We were told that approaching along the valleys either north-east from Ajaccio or from the North is risky unless the weather is perfect and we were advised that the best route was from the South-east, over lower ground, and that getting clearance through the restricted areas there should not be a problem. An outing for another occasion, and our trip to Corte had to be by car through spectacular scenery but sometimes heavy traffic on the winding mountain road.

We anticipated arriving about the same time as our two sons, who were coming by Air France / Air Corsica via Paris (we had left home simultaneously). An exchange of text messages revealed that they were, however, still at Paris Orly. Their flight to Charles de Gaulle had been delayed, they missed the connection at Orly and Henry’s suitcase had disappeared—along with 19,999 others on that day alone because of a scanner malfunction at Charles de Gaulle! After chasing us around Europe for a while the bags finally caught up with us at home 28 days later.

With the family re-united just before midnight we had an excellent week in Corsica and Henry discovered the meaning of travelling light. Sadly, our plan to fly to Corte in the interior was thwarted by it being closed until the end of the year for renovation, but we did tap into local knowledge about the best way to get there. Corte is at 1,100 feet AMSL with peaks up to around 6,000 feet immediately to the West and 3,000 feet to the East. We were told that approaching along the valleys either north-east from Ajaccio or from the North is risky unless the weather is perfect and we were advised that the best route was from the South-east, over lower ground, and that getting clearance through the restricted areas there should not be a problem. An outing for another occasion, and our trip to Corte had to be by car through spectacular scenery but sometimes heavy traffic on the winding mountain road.

Max and Henry departed back to university at the end of the week. With a line of thunderstorms spreading across northern Italy and heavy rain forecast for our day in Venice, we decided to pop across to Elba instead.

A tip about returning a car at Ajaccio: it can take ages if a commercial flight has just delivered a load of passengers to the doors of the car hire offices; there seems to be no facility for a quick drop-off, so leave plenty of time (it took us about an hour). Hint: wave the folder of hire papers at the receptionist who, realising you are returning, not collecting, will try to hurry things along; after all, they need the vehicles!

And one thing about fuelling with Avgas at Ajaccio: if you do not have a BP Avgas card you may have a long wait for an attendant to come with a credit card terminal (in +32°C in our case). The wait will be particularly long, as across France as a whole, if you choose to refuel between 12:45 and 14:15, which straddles the sacred period of déjeuner. The price, however, was only €1·22 per litre and landing and seven days parking a mere €45, which was compensation of sorts.

A tip about returning a car at Ajaccio: it can take ages if a commercial flight has just delivered a load of passengers to the doors of the car hire offices; there seems to be no facility for a quick drop-off, so leave plenty of time (it took us about an hour). Hint: wave the folder of hire papers at the receptionist who, realising you are returning, not collecting, will try to hurry things along; after all, they need the vehicles!

And one thing about fuelling with Avgas at Ajaccio: if you do not have a BP Avgas card you may have a long wait for an attendant to come with a credit card terminal (in +32°C in our case). The wait will be particularly long, as across France as a whole, if you choose to refuel between 12:45 and 14:15, which straddles the sacred period of déjeuner. The price, however, was only €1·22 per litre and landing and seven days parking a mere €45, which was compensation of sorts.

Now, to pre-flight planning: there is a weather station on Elba, on the South-east peninsula. It does not appear in the aviation weather station lists but is featured on the Air Navigation Pro map. The METAR was almost always IFR during our visit, and there is no TAF. The conditions at this station do not, however, bear any relation to the weather at the airport. Nor, for that matter do any other published weather reports. So we telephoned Elba ATC and were told that it was great weather there: few clouds around 2,000 feet and all the nines, so we said: “see you soon” and set off.

Leaving Ajaccio we expected to be given a routing via a sequence of VRPs but the controller just asked: “where would you like to go?” The answer was dictated by keeping clear of cloud (carburettor and no AI) so we gave him a couple of turning points and wiggled our way toward them. The Corsican peaks were, as usual, covered in cloud and the thermals off the mountains were fierce. Not wanting to get bounced around too much we elected to fly around the coast, crossing the northern peninsula just north of Bastia for the 35 nm crossing to Elba airport.

Leaving Ajaccio we expected to be given a routing via a sequence of VRPs but the controller just asked: “where would you like to go?” The answer was dictated by keeping clear of cloud (carburettor and no AI) so we gave him a couple of turning points and wiggled our way toward them. The Corsican peaks were, as usual, covered in cloud and the thermals off the mountains were fierce. Not wanting to get bounced around too much we elected to fly around the coast, crossing the northern peninsula just north of Bastia for the 35 nm crossing to Elba airport.

LI D 29 was active from 500 feet AMSL to FL 050 so, with its eastern border only 7 nm from Elba airport, we elected to fly under it. Just as well: Elba eventually loomed into view like Skull Island from ‘King Kong,” covered with cloud to under 1,000 feet extending several miles out to sea, with patches of mist down to sea level. Rounding Capo di Poro, Elba ATC casually asked us to report visual on the airfield. Well, we knew where to look for it: the end of the runway was less than 700 metres North-west of the beach and we had a clear view all around the edge of the bay, but a blob of cloud had decided to nestle into the valley and snuggle up to the airfield less than 500 feet above it. Holding off near the mouth of the bay (there were boats further in), we dropped down to a couple of hundred feet to have a peak under the cloud layer, reported visual and scooted left downwind for 16 avoiding the 550 foot hill 700 m to the east of the airfield and the 600 foot one less than 1 nm directly to the north. The lesson here is ‘weather forecasting’ has no meaning in Elba. There are the current conditions and an uncertain future. ATC will tell you the weather when you ‘phone, but the conditions can change rapidly and, if you are flying at low level, radio communication is virtually blocked until you are in line of sight to the South. So take plenty of fuel.

Another reason for taking lots of fuel is the price of Avgas: a whopping €3·54 per litre, even Jet-A1 was €1·32 (in contrast landing, take-off and three days parking was a reasonable €33). We needed to leave with full tanks so we topped the main, 110 litre, tank with the oro liquido (the 50 litre long-range tank was still full), reckoning that would get us at least to Lyon Bron with a couple of hours in reserve.

Weather reports for the day before departure indicated fog clearing around 09:00 after which it was to be a sunny day. Being Elba, the fog didn’t really clear all day: the cloud was virtually down to the ground. Get what we mean about weather forecasting in Elba? Nevertheless, we used the day usefully, bicycling to the other side of the island and back and sipping cocktails by the beach. Can’t understand why Napoleon wanted to get away. But it’s obvious why it took him so long.

Weather reports for the day before departure indicated fog clearing around 09:00 after which it was to be a sunny day. Being Elba, the fog didn’t really clear all day: the cloud was virtually down to the ground. Get what we mean about weather forecasting in Elba? Nevertheless, we used the day usefully, bicycling to the other side of the island and back and sipping cocktails by the beach. Can’t understand why Napoleon wanted to get away. But it’s obvious why it took him so long.

The day of departure looked pretty good but the visibility over the mediterranean turned out to be dreadful, at least until we were North-abeam Corsica. 170 nm of stick flying in very hazy conditions was going to be quite demanding but we had taken the precaution of rigging Jennie’s iPad mini running Air Navigation Pro in 3-D EFIS mode on the panel, which worked fine and was very reassuring. We stayed at 400 feet for the first 30 nm or so to keep visual on the sea, nonetheless.

Because of severe weather moving East across southern France and the northern mediterranean, a direct route over the restricted areas was impossible: the cloud was on the ground and the cumuli were towering well above our ceiling. Accordingly, we had planned to take the low-level VFR route around the coast from Saint Tropez to WA, South of Nimes, then directly North. It takes longer but it is well worthwhile: it is a spectacular coastline, especially enjoyable because the radar services will keep you between 500 and 1,000 feet.

Because of severe weather moving East across southern France and the northern mediterranean, a direct route over the restricted areas was impossible: the cloud was on the ground and the cumuli were towering well above our ceiling. Accordingly, we had planned to take the low-level VFR route around the coast from Saint Tropez to WA, South of Nimes, then directly North. It takes longer but it is well worthwhile: it is a spectacular coastline, especially enjoyable because the radar services will keep you between 500 and 1,000 feet.

Flying up the Rhone valley, Dijon was showing overcast at 600 feet or so with rain and Darois is 850 feet higher, so we stopped at Lyon Bron, our first alternate, for fuel (now you need a Total Avgas card or a longish wait to pay by carte de credite) and then pushed on to Toussus Le Noble in the outskirts of Paris—not an easy flight across the Burgundy hills with low cloud and rain and another reminder of the benefits of a fully equipped aircraft with fuel injection.

Toussus Le Noble advertises customs, but only if, and we have the email and the NOTAM data to prove it, you are flying within Schengen. The key omission is ‘immigration.’ So, for the flight home the day after our meeting in Paris, we cancelled our flight plan from Toussus to Elstree and re-filed from Le Touquet that, like Calais, requires only two hours prior notice for la Douane. On arrival at Toussus, however, we were told by the very accommodating GA manager that flying direct to the UK was not a problem. She offered to file a flight plan by telephone and ‘phoned the local ATSU, who confirmed that we already had a plan filed from Toussus and could depart immediately (probably the plan that we had cancelled the night before). Anyway, in the aircraft with the engine running ATC could not find the plan and we went to Le Touquet anyway, still confused about what the arrangements at Toussus really were. Subsequent enquiry confirmed that, because Toussus is not a designated ‘port of entry,’ it is not legal to fly direct to a non-Schengren country, although a bit or rule-bending may have been done in the past!

Toussus Le Noble advertises customs, but only if, and we have the email and the NOTAM data to prove it, you are flying within Schengen. The key omission is ‘immigration.’ So, for the flight home the day after our meeting in Paris, we cancelled our flight plan from Toussus to Elstree and re-filed from Le Touquet that, like Calais, requires only two hours prior notice for la Douane. On arrival at Toussus, however, we were told by the very accommodating GA manager that flying direct to the UK was not a problem. She offered to file a flight plan by telephone and ‘phoned the local ATSU, who confirmed that we already had a plan filed from Toussus and could depart immediately (probably the plan that we had cancelled the night before). Anyway, in the aircraft with the engine running ATC could not find the plan and we went to Le Touquet anyway, still confused about what the arrangements at Toussus really were. Subsequent enquiry confirmed that, because Toussus is not a designated ‘port of entry,’ it is not legal to fly direct to a non-Schengren country, although a bit or rule-bending may have been done in the past!

Overall, a hugely enjoyable, sometimes challenging, journey. The DR401 160, with all the attributes of the superb Robin airframe acquitted itself admirably. The outstanding visibility is always a joy on these trips and the stable yet responsive handling makes for a relaxing flight. Compared to the diesels that we are more used to, the take-off run with the Lycoming engine and fixed pitch propellor is leisurely and the climb is relaxed but the 160 turned in a cruise of around 120 kts indicated airspeed at 2,500 rpm and averaged 30 litres per hour over the whole trip at a take-off weight of around 905 kg (about 145 kg under MTOW). Noisier and rougher than a diesel, the Lycoming engine never failed to start promptly and regular attention to engine management kept the pilot alert. Our thanks to Robin Aircraft for lending us the aircraft and we look forward to collecting our DR401 155CDI from Darois!